How to Ferment Miso

Mastering the Art of Traditional Japanese Paste

Miso is a fundamental ingredient in Japanese cuisine, providing a unique umami flavor that is both rich and savory. Rooted in centuries-old techniques, miso's distinct taste and nutritional profile are the result of a fermentation process involving soybeans, a grain such as rice or barley, salt, and a fermentation culture known as koji. The art of crafting miso is meticulous and rewarding, with the fermentation period ranging from a few months to several years, leading to a wide spectrum of flavors and colors, from sweet and light to salty and deep brown.

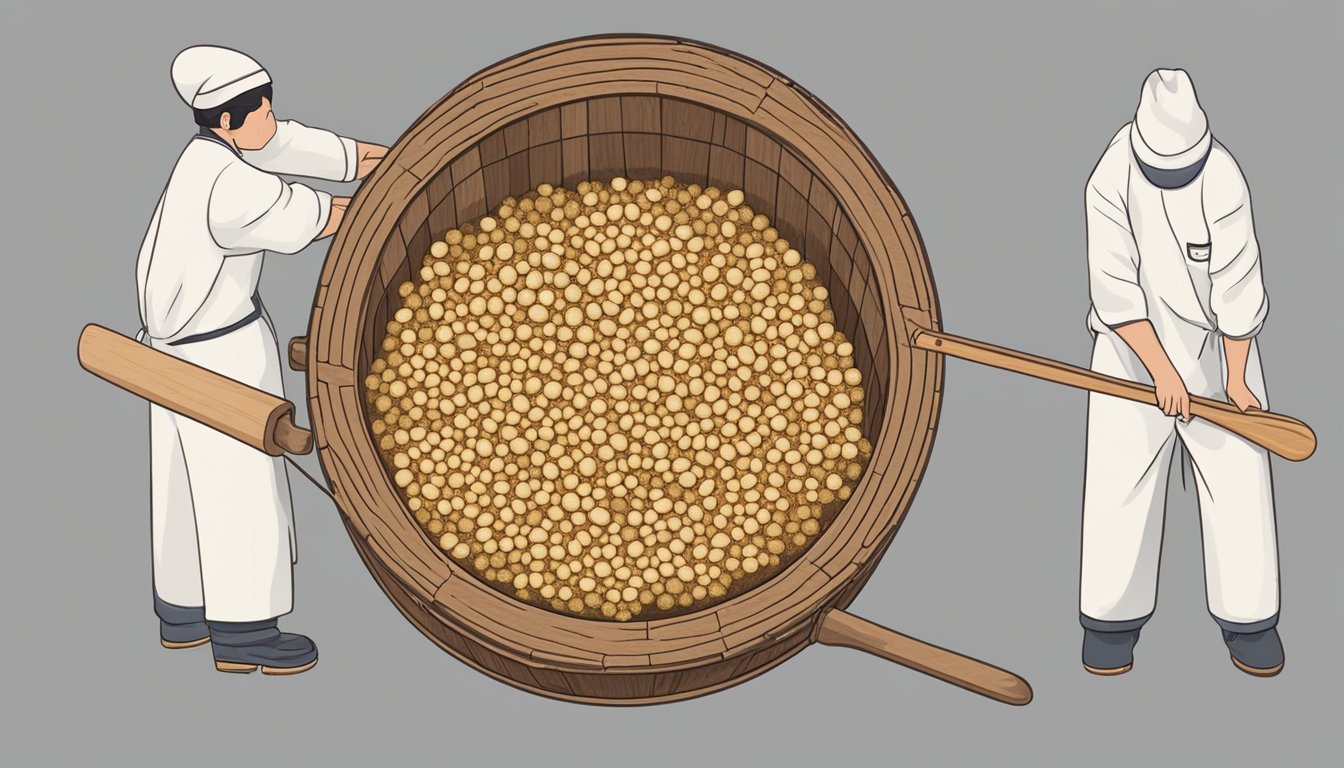

The fermentation of miso is a transformative journey influenced by variables such as temperature, duration, and ingredient ratios. At the start, the soybeans are cooked until tender and then mixed with koji—steamed grains inoculated with Aspergillus oryzae spores. This mixture is combined with salt to create an environment where beneficial microorganisms can thrive while deterring unwanted bacteria. In a carefully controlled setting, the miso ferments over time, developing its characteristic flavor profile.

Throughout the fermentation process, meticulous care is required to ensure a successful batch of miso. Steps include compressing the paste to eliminate air pockets that could spoil the product and maintaining the right environmental conditions. The result is a versatile paste that is integral to numerous dishes, contributing an unrivaled depth of flavor that is synonymous with traditional and modern Japanese cooking.

Understanding Miso and Its Origins

Miso is a traditional Japanese seasoning produced by fermenting soybeans with salt, grains, and koji. In its rich history, it has evolved into various types, each with distinctive flavors and uses.

What Is Miso?

Miso is a fermented bean paste integral to Japanese cuisine. It’s primarily made from soybeans, a type of legume, which are fermented with salt and a cultured grain called koji. Koji introduces the necessary enzymes to initiate and sustain the fermentation process. Miso can be made using different grains, such as rice or barley, affecting its flavor and color.

Historical Background

Originating in Japan, miso's earliest documentation was in the Heian period (794 - 1185). Its production process shares similarities with that of making a sourdough starter, relying on microbial action to achieve its distinctive taste. Over the centuries, traditional miso was crafted in wooden barrels, with the fermentation spanning months to years, contributing to its deep umami flavor.

Types of Miso

Different regions in Japan produce distinct miso types, which can be categorized based on:

Grain Type: Rice (Kome-miso), Barley (Mugi-miso), and others.

Color: Ranges from white (Shiro-miso) to red (Aka-miso) to mixed (Awase-miso).

Flavor: Varies from sweet and mild to salty and strong.

Grain Type: Rice

Common Name: Kome-miso

Characteristics: Sweet, mild

Grain Type: Barley

Common Name: Mugi-miso

Characteristics: Robust flavor

Grain Type: Mixed

Common Name: Awase-miso

Characteristics: Balanced taste

Each type has a specific application in Japanese cooking, adding a depth of flavor to dishes, including soups, marinades, and sauces.

The Science of Fermentation

Fermentation is a biochemical process involving microorganisms that break down complex organic compounds into simpler molecules, often producing flavors unique to fermented foods like miso. This section explores the specific stages and biological participants that contribute to miso's distinctive taste and texture.

Fermentation Process

Fermentation in miso begins with the inoculation of cooked beans with koji mold, a process that initiates the breakdown of starches and proteins. Over the course of several months to years, koji enzymes work to convert these complex molecules into fatty acids, amino acids, and simple sugars. This transformation not only enhances flavor but also increases the nutritional value of miso. Temperature and duration play critical roles; fermenting at varying temperatures can impart different flavor profiles, while longer fermentation times typically develop a deeper taste and darker color.

Role of Koji

Koji is cultivated from the Aspergillus oryzae mold, which is pivotal in the production of miso. This mold secretes enzymes such as amylase and protease, which are essential for breaking down starches and proteins, respectively. The enzyme activity is what triggers the transformation of the base ingredients into the complex, umami-rich flavor profile that miso is known for. Without koji, traditional miso fermentation would not be feasible.

Microorganisms Involved

While the koji provides enzymes for the initial stages of miso fermentation, a host of other microorganisms, including bacteria and yeast, become involved in later stages. The presence of lactic acid bacteria and other microbes contribute additional layers of taste and complexity, and also help preserve the miso. Controlled mold growth, primarily through the careful management of temperature and humidity, ensures a safe fermentation process without unwanted contamination.

Preparation for Miso Making

The preparation for miso making is a crucial step in creating a flavorful and well-fermented product. Proper selection of ingredients, preparation of beans, and cooking of grains and beans lay the foundation for successful miso fermentation.

Selecting Ingredients

For a traditional miso, three essential ingredients are needed: soybeans, rice koji, and salt. The quality of these ingredients greatly impacts the flavor and quality of the miso.

Soybeans: Choose organic soybeans for their non-GMO properties and better flavor profile. The legume is the base for miso's texture and taste.

Rice Koji: This is steamed rice that has been inoculated with Aspergillus oryzae. It is the fermenting agent that breaks down the proteins and fats in the soybeans.

Salt: Salt acts as a preservative and also influences the fermentation rate. Use sea salt for a natural choice without additives.

Preparing the Beans

Soybeans need thorough cleaning and soaking before use.

Cleaning: Rinse the soybeans to remove dirt or impurities.

Soaking: Immerse soybeans in plenty of water, as they will expand to approximately double their size. A standard practice is to soak them for 18 to 24 hours.

Cooking Grains and Beans

After the beans are prepared, one must cook them until soft while preparing the grains.

Soybeans: They should be cooked until mashable but remain firm to the touch. This usually requires boiling for **2

Tools and Equipment

Gathering the correct tools and equipment is essential for successful miso fermentation. Ensuring that these items are clean and suitable for the process will contribute to the quality of the final product.

Choosing the Right Equipment

Fermentation Vessel: The vessel in which miso is fermented is critical to the process. One should opt for a 1-gallon sterilized container, which can be a glass jar or a ceramic crock. It is imperative that the container does not react with the miso paste during the months it will spend fermenting. Glass is often preferred for its non-reactive qualities.

Muslin or Cloth: A piece of muslin or a similar breathable cloth is needed to cover the mouth of the fermentation vessel. This allows for airflow while protecting the miso from contaminants.

Measurement and Weights

Kitchen Scale: Accurate measurements are key in fermentation. A kitchen scale is used to weigh the ingredients such as soybeans, koji, and salt, ensuring exact proportions.

Weights: A weight is necessary to press down the miso in the fermentation vessel, aiding in the removal of air pockets and creating an anaerobic environment. A clean stone or a specially designed fermentation weight can serve this purpose. Choose a weight that fits well within the vessel and covers most of its mouth.

The Making of Miso

Miso making combines tradition with fermentation science, requiring carefully measured ingredients and a controlled environment to yield the savory Japanese condiment.

Mixing the Ingredients

The primary ingredients for miso are beans (often soybeans), salt, and koji (a culture derived from rice, barley, or soybeans). One begins by soaking the beans in water until they are fully hydrated. The beans are then cooked until soft and mashed into a paste. Separately, koji is mixed with salt to create a saline solution which is then thoroughly combined with the bean mash. For a basic recipe, ratios are crucial to ensure proper fermentation.

The Fermentation Stage

Once mixed, the miso paste is transferred to a fermentation vessel, and care is taken to remove any air pockets, as they can lead to unwanted microbial growth. Weights are placed on top of the mash to keep it submerged, reducing oxidation and promoting an anaerobic environment necessary for fermentation. The vessel is then stored at room temperature, and the fermentation time can range from a few months to several years depending on the desired flavor profile.

Monitoring the Fermentation Process

Regular monitoring is essential to prevent mold formation. The surface should be kept clean, and any growth should be removed if spotted. It's also important to occasionally stir the miso paste to distribute the salt and koji evenly. As the fermenting miso matures, it can be tasted to assess whether its flavor has developed sufficiently. Once fermentation is complete, the miso can be stored in a refrigerator to halt the process.

Storing and Maturing Miso

When fermenting miso, the storage conditions and maturation process are crucial for developing its flavor and ensuring its preservation. Correctly storing and aging miso will allow it to transform into a rich and complex seasoning essential for various culinary uses.

Storage Conditions

During the fermentation process, miso should be stored in an environment that maintains a stable temperature to prevent unfavorable changes in taste and texture. Optimal storage conditions include:

Temperature: Maintain a consistent temperature between 59°F and 77°F (15°C and 25°C) for the initial fermentation phase.

Refrigeration: Once the initial fermentation phase is complete, transferring miso to a refrigerator can slow down the fermentation process and stabilize the flavor. The refrigerator temperature should be set to below 41°F (5°C).

Environment: Miso should be kept in a container with an airtight seal to protect it from contaminants and moisture. The chosen area should be dark with minimal temperature fluctuations.

Maturation Process

The maturation process of miso plays a vital role in the development of its flavor profile. Factors influencing miso maturation include:

Fermentation Time: Miso typically requires a fermentation period ranging from a few weeks to several years. Shorter fermentation periods result in milder flavors, while longer periods lead to deeper, more intense tastes.

Conditions Monitoring: Regularly check the miso for any signs of spoilage such as mold or off-odors. A benign white mold might form on the surface; it can be scraped off as it does not affect the miso's quality.

Temperature Adjustments: During the aging process, slight adjustments to the storage temperature can be made to fine-tune the miso's flavor development. Lower temperatures slow down the fermentation, prolonging the maturation period and potentially enhancing flavor complexity.

Flavor, Texture, and Usage

In understanding miso, one must consider the complexities of its flavors, the richness of its textures, and the versatility in its culinary applications.

Analyzing Miso Flavors

Miso's flavor profile is deeply influenced by its fermentation process, where the length and condition play pivotal roles. One can find a spectrum from sweet miso, which is lighter and less aged, to deep umami-rich variants that result from extended fermentation periods of up to three years. The taste can vary from salty to savory, with certain types achieving an almost earthy sweetness. This broad range allows miso to be used to enhance the flavor in sauces and miso soup, adding a distinct aroma that is both rich and satisfying.

Understanding Textural Variations

The texture of miso paste also differs based on fermentation duration and ingredients. A smooth, creamy texture is typically found in shorter-fermented miso, while longer fermentation leads to a thicker consistency that might require dilution when cooking. Textural variation affects not only the tactile experience but also how miso integrates with other ingredients, determining whether it can be used for delicate marinades or robust stews.

Culinary Applications

Miso's culinary applications are numerous, encompassing far more than the well-known miso soup. Its umami quality makes it a go-to ingredient for sauces, dressings, and marinades, enhancing the flavor profiles of vegetables, proteins like tempeh, and even adding complexity to confectionery. Chefs employ miso to impart a savory backbone to dishes, where it contributes a unique taste and aroma that cannot easily be replicated by other ingredients.

Health Benefits and Nutritional Information

Miso, a fermented soybean paste, is not only a staple ingredient in Japanese cuisine but also a treasure trove of nutritional benefits. This section unpacks the nutritional content and health advantages associated with consuming miso.

Nutritional Content

Miso Paste (per tablespoon, approx. 18g):

Nutrients: Calories

Amount: 34 kcal

Nutrients: Protein

Amount: 2g

Nutrients: Carbohydrates

Amount: 4.3g

Nutrients: Fiber

Amount: 0.9g

Nutrients: Fats

Amount: Trace amounts

Nutrients: Sodium

Amount: Varies by type

Miso is rich in proteins, essential amino acids, and provides a good mix of vitamins and minerals like vitamin K, manganese, and zinc. The fermentation process not only enhances its flavor but also increases the bioavailability of these nutrients, making them easier for the body to absorb.

Health Advantages of Miso

The health benefits of miso are numerous. Due to its fermentation, miso is abundant in probiotics, which are beneficial for gut health and overall immune function. Miso has also been linked to a reduced risk of certain cancers such as lung, colon, stomach, and breast. Furthermore, despite its high sodium content, studies suggest that miso does not raise the risk of stomach cancer as other high-salt foods might.

It provides essential fatty acids and boasts antioxidant properties that can help reduce oxidative stress in the body. The presence of amino acids in miso is important for muscle repair and energy production, while vitamins and minerals play various roles in maintaining bodily functions.

Regular consumption of miso may provide a complex nutrient profile that can be a valuable part of a balanced diet.

Innovative Recipes and Variations

Fermenting miso at home offers endless possibilities for culinary experimentation, allowing enthusiasts to adapt traditional techniques to create innovative recipes and contemporary infusions that align with personal tastes and available ingredients.

Homemade Miso Recipes

When one ventures into making homemade miso, the traditional Japanese method provides a reliable blueprint. A basic miso recipe involves rice koji, soybeans, and salt, yet the craft of miso-making allows for personal touches and the use of various legumes, grains, and infusion components. For instance, one may substitute soybeans with other beans such as chickpeas or black beans to create unique flavors and textures.

For those seeking a simple homemade miso, the process typically involves:

Soaking and cooking the chosen beans until soft.

Mashing the beans and mixing thoroughly with rice koji and salt.

Packing the mixture into a sterilized jar, ensuring it is compressed to remove air bubbles.

Tip: Wrap the surface with parchment paper or plastic to minimize exposure to air and mold formation.

Contemporary Miso Infusions

The adventurous cooks have expanded the horizons of miso far beyond its traditional confines, infusing it with a dazzling array of flavors. Innovations such as pumpkin seed miso or orange miso reflect these trends, where chefs infuse the miso paste with seeds, citrus zests, or even cacao to diversify the palate of Japanese cuisine.

When creating a contemporary miso infusion, chefs may blend the following ingredients into their miso base:

Vegetable purees: Adding sweet potato or pumpkin puree for a sweet and earthy undertone.

Seeds and nuts: Incorporating ground pumpkin seeds, sesame seeds, or walnuts for added texture and flavor complexity.

Each unique ingredient introduces a new dimension to the traditional miso, which can be used in customary dishes such as miso soup or as inventive spreads and marinades.

Troubleshooting Common Miso Issues

Miso fermentation requires careful management to avoid issues such as contamination or an imbalanced flavor profile. The following subsections provide guidance on maintaining the ideal conditions for creating quality miso.

Preventing Contamination and Spoilage

One must prioritize cleanliness to prevent contamination and spoilage during miso fermentation. Here are key strategies:

Sanitize Equipment: Ensure all utensils, containers, and work surfaces are thoroughly sanitized before starting the fermentation process.

Minimize Oxygen Exposure: Oxygen can introduce unwanted bacteria and molds. Seal the fermented soybean paste adequately, using parchment paper or plastic wrap pressed directly onto the surface of the miso.

Control Moisture: Excessive moisture encourages undesirable microbial growth. If tamari (the liquid that sometimes forms on top of the miso) pools, it should be mixed back into the paste to prevent mold formation.

Regular Checks: Inspect the miso periodically for signs of mold. If found, one should gently scrape away affected areas.

Adjusting Fermentation Conditions

The environment and duration are vital to the outcome of fermented miso. Here's what to consider:

Temperature: Miso should be stored in a cool, dark place to maintain a consistent temperature conducive to fermentation.

Timeframe: Depending on the desired flavor intensity, fermentation time can range from 6 months to several years. Longer fermentation leads to a richer, more complex flavor.

Monitor Development: Taste the miso at intervals to judge whether the fermentation conditions are producing the desired flavor profile.

By following these specific measures, one can greatly reduce the risks of miso fermentation and help ensure successful production of this traditional fermented soybean paste.